DreamMaker Bath and Kitchen

- (561) 459-1004

- email us

- Jupiter, Florida, United States

JUPITER, FL – June 29, 2017 – “I like to go fast. I like it a lot.” We are standing in the middle of the EMS Racing shop speaking with team owner Scott Sharp, who is also one of the team’s drivers. We are standing beside his racecar chassis, which in its current stripped-down shop condition resembles not so much a car, but rather a small jet.

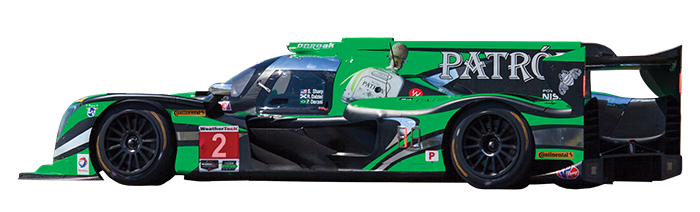

Engineered by Onroak Automotive in Le Mans, France to be the most aerodynamic, competitive prototype on the International Motor Sports Association (IMSA) racing circuit, and constructed of state-of-the-art carbon fiber in order to be extremely lightweight, Sharp’s cars (there are two) command attention. You cannot look away.

At any moment, it seems as if they will roar to life of their own accord.

And this is just viewing the stripped-down chassis, without the distinctive neon green wrapped front- and back-ends attached. Add on the sponsor, Tequila Patron’s branded bee artwork and they become wicked – out to sting the competition.

That relationship with Tequila Patron is a large point of pride for Sharp. Not only is he one of the few owner/drivers in Sports Racing, but he is also one of the few owners to have such a long and lasting relationship with a sponsor. “We’ve been with Tequila Patron for 10 years now,” Sharp says with a huge smile. “In racing, especially, that is a long time for a partnership and we’re still going strong and having fun.” In fact, one of the EMS team drivers, Ed Brown, also happens to be the President and CEO of Patron Spirits International.

For Sharp, it is the relationships that matter, family, and yes, going fast. Very, very fast.

Motor Oil In The Blood

Everything about Sharp is built for speed – from his gait, to his intelligent conversation, to his compact, athlete’s physique – and it isn’t a surprise. He hails from a rich racing past. It is almost as if it is in his very DNA.

His father, Bob Sharp, was himself a racecar driver, winning the Sports Car Club of America’s national championship six times between 1967 and 1975. He is also the man credited with introducing actor Paul Newman to competitive driving in 1971. Newman subsequently joined Sharp’s team, later partnering with him to form Newman-Sharp Racing.

“I don’t even remember my first time at a track,” Sharp says, “But I was six months old and it was at Lime Rock with my Dad. As I was growing up, I was always there, traveling with my Dad and helping out with the team. I was eight when my Dad retired from active racing and concentrated solely on managing the team. That was also when I started go-carting, so everything fit together. Now kids can start go-carting at age five, but back then you had to be eight.”

Sharp literally grew up on the tracks.

“Cars are so much more expensive to drive than carts, but I was fortunate because with the team, there were always left-over cars. It was actually more economical for me to jump up from carts into cars,” Sharp says with a real sense of gratitude. “By the time I was 18, I had competed in 20 races.”

But, it wasn’t all fast cars and movie stars. He chuckles. “My Mom is a teacher and she put on the brakes. She insisted that I go to college and get a degree. So I went to Babson College in Boston, which is a small business school. But by my junior year, I was racing professionally.”

Mom’s foresight; however, has served him well. He now owns his own race team with 40 employees and is responsible for intricate logistics and mind-boggling moving parts. His business acumen has seen him through Indycar and various teams until finally reaching his own satisfying partnership with Tequila Patron and the IMSA Endurance Racing Circuit.

PROTOTYPICAL RACE CAR:

What is the difference between a prototype car, such as Sharp’s, and an Indycar? Not much in terms of performance. “We’ve tested at the same tracks as Indycars,” Sharp says. “In terms of acceleration, braking, etc. we are within a couple seconds of each other.”

The differences are in the physical appearances of the cars. On IMSA league vehicles, the wheels are covered and the cockpit is closed. On Indycars, the wheels are open and the driver is exposed. “Indy is trying to figure out a way to shield the driver’s helmet,” Sharp explains. •

Controlling Moving Parts: Human & Machine

In one three week period alone, the EMS team has to run a 12-hour endurance and sprint race in Sebring, Florida (March 18) and then load all of their equipment and both of their cars into three rigs for a trip to Long Beach, California for the Grand Prix of Long Beach (April 7-8).

The rigs themselves are travelling replicas of the race shop. “When we are out, there is no telling what can happen and we have to be able to identify and fix it at a moment’s notice,” Sharp explains. Two stories each, the rig’s lower floors contain cabinets filled with tools and work surfaces for computers, and cabins for the crew. The upper floors house the cars.

Being able to communicate with the cars is vital. During the races, “We have telemetry on the cars that sends 300 to 400 channels of information to the crew every millisecond – so basically the car is alive,” Scott says sketching his hands through the air as he talks. “The team in the pit follows our car around every lap and this is why we have so many people [on the road] because there is the whole engine team and they are looking at every temperature and pressure and performance angle of the car; and the chassis engineers are watching exactly how you are driving, including the temperature and components like the throttle and brakes. Then you’ve got the actual engineer for the car, paying attention to what changes might come up in the next pit stop – they are seeing every little thing that is going on in the car, in real time.”

And it isn’t just the car that the crew is monitoring. When driving, the EMS drivers all wear heart monitors to keep track of their personal heart rates for training purposes. It is almost as if men and machines become one – with the car’s average speed ranging between 130 and 160 mph and the drivers’ heart rates “running between 145 and 165 for the entire time that you are in the car,” Sharp says. “So, by wearing the monitors, we have learned that cardio training is hugely important. Driving is very cardiovascular.”

He continues, “I don’t think people understand the level of fitness it takes to drive. Not only do we do cardio training, we also have to have stability in the core, the lats, back, and shoulders to hold ourselves in because of the G-forces that the cars pull.”

When stepping on the acceleration, these cars can reach top speeds of over 200 mph, “and then we have to immediately brake down to 45 mph,” Sharp explains. “The cars could actually go a lot quicker but they are designed with maximum down-force, meaning that the air pushes the car down on the track. The braking efficiencies are just incredible. You are going 200 mph and it is 100 yards to a corner and you wait until the last possible moment. What’s even more impressive is there’s so much down-force, you could run our cars inverted if you could find a way to get them upside down.” That means that the drivers are subjected to the same G-forces that fighter pilots experience. To be top competitors, they must be in top physical condition.

Fitness is also important considering the fact that 10 pounds of weight is considered to be the equivalent of 1/10th of a second. “It may sound funny,” Sharp says, “but we fight for tenths of seconds. Most drivers tend to be in the 145 to 165 pound range.” Factor in that the average pit stop is just 25 seconds long, including driver change, and it becomes clear that the men and women who compete in racing must be disciplined athletes.

Jupiter: NOT Indy or Daytona

So how is it that the man who got his start racing Indy cars and has won the famous Daytona 24-hour Endurance race came to live in Jupiter?

“Good question,” Sharp says with a laugh. “Actually, I’ve been here for 14 years. Of course, I started in Connecticut with my family growing up. I moved to Indy when I was racing with the Indycar circuit. But we had friends who lived in Jupiter and we would vacation with them. Vacations led to wintering down here and I would commute back and forth. Then, one year, it snowed in Indianapolis in March, and I thought, ‘I can’t do this anymore. Why are we still here?’ So, we moved to Tequesta and have never regretted it. I feel so blessed to live where we do. I’m always outside trying to take advantage of it.”

He continues, “Besides that, from mid-November to mid-March, Florida is the only place in the United States to test [run the car’s] tire temperature, engine temperature, etc. Here, we don’t have to get on a plane. We drive to Daytona, Sebring, run down to Homestead if we need to…and now that we’ve gotten to know the tracks, they will schedule time for us around the other regularly scheduled events.”

A Driving Passion

Florida’s year-round racing climate also allows Sharp to maximize crucial family time. His children travel with him, just as he travelled with his father. His seven-year-old son is learning the finer points of go-carting. “He started a few years ago and wasn’t really getting it,” Sharp says. “Now, when I tell him how to take a corner, he listens and actually does it. It has been great to see his progression.” Who knows? The future may hold another Sharp racing champion. “Maybe so,” he says with a chuckle. “We’ll see what he wants to do.”

“Everybody told me that there was no way that I could do what I do [be a driver/owner]. And I said, ‘My Dad did both’ and I grew up around it, so to me it was very second nature. Actually, it has worked out tremendously well. It gets chaotic at times. No one quite understands the level of details it takes to move 40 people around the planet. But the driving passion for me is when you get in the car. There’s nothing like that in the world. The rest of the world is shut out. For the next couple of hours – whether the car is fantastic or whether it is so-so – it is what it is and you’ve gotta find a way to drive it as fast as you can drive it. That is still the motivation.”